Foundations of motivation

Dr Germano Gallicchio

Lecturer in Psychophysiology and Cognitive Neuroscience

School of Psychology and Sport Science, Bangor University, UK

profile | research | software | learning resources | book meeting

On a computer press F11 to de/activate full-screen view.

For smartphone and review: Bottom left menu → Tools → PDF Export Mode.

For pdf document: use “learning resources” link above.

Last modified: 2025-11-24

QR code to

these slides:

PIN

Agenda

- some foundational concepts in motivation

- a mixture of theory and intuition

- basics of Cognitive Evaluation Theory

- basics of Achievement Goal Theory

- basics of Attribution Theory

- experience collecting self-report data to measure a motivation construct

Questionnaire activity (part 1)

Fill in the questionnare “Task and Ego orientation in Sport Questionnaire” (Duda, 1989). There is no right or wrong answer.

We will compute the scores (page 2) later in the session and we will discuss what the scores mean

Intuitive understanding

Etymology (origin of the word) of motivation: from the Latin “motus” meaning “motion”

A working definition for now can be “what moves somebody”

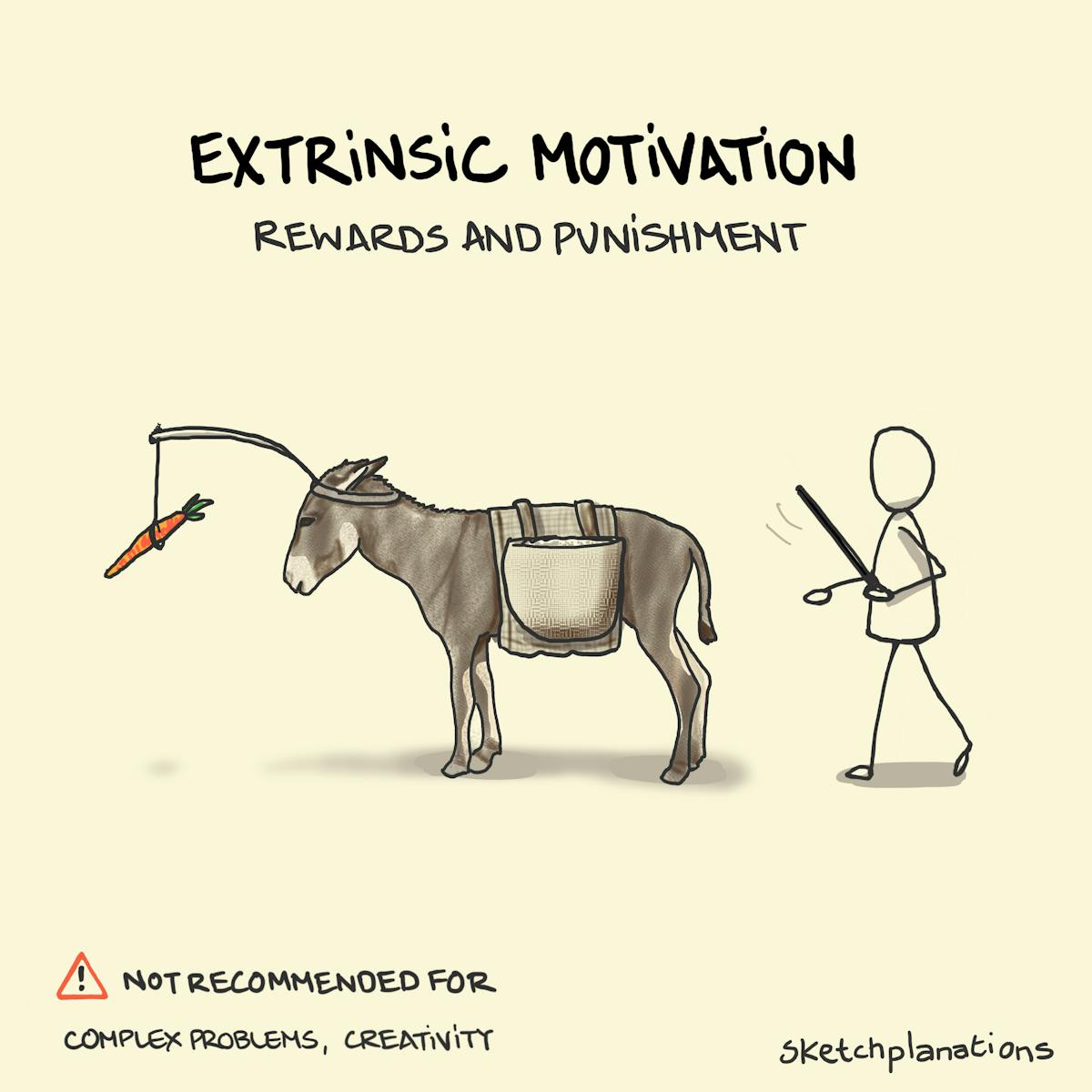

Analogy of “stick and carrot”

Approach vs avoidance

Distinction used across several motivation models:

Intrinsic vs extrinsic motivation

| Intrinsic | Extrinsic | |

|---|---|---|

| purpose: activity… | …undertaken for its own pleasures | …undertaken for instrumental benefits |

| reward: | experience itself | social or objective rewards (e.g., trophies, praise) |

| competitive pressure: | less pressure (concerned with the experience) | more pressure (concerned with the benefits) |

Examples of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation:

- Intrinsic: running because you enjoy the sensation and challenge

- Extrinsic: running to qualify for team selection, or to earn a bonus

(same behavior, but different motivation)

Which one is better?

Intrinsic is often the ideal type

Theoretically distinct…

…but practically interacting in real life: more of one is associated with less of the other

Importantly, one can turn into the other.

Anectode of the old man and the kids

The reward overjustified the activity. This phenomenon is called overjustification effect.

An old man lived alone on a street where boys played noisily every afternoon. The din annoyed him, so one day he called the boys to his door. He told them he loved the cheerful sound of children’s voices and promised them each 50 cents if they would return the next day. Next afternoon the youngsters raced back and played more lustily than ever. The old man paid them and promised another reward the next day. Again they returned, whooping it up, and the man again paid them; this time 25 cents. The following day they got only 15 cents, and the man explained that his meager resources were being exhausted. “Please, though, would you come to play for 10 cents tomorrow?” The disappointed boys told the man they would not be back. It wasn’t worth the effort, they said, to play all afternoon at his house for only 10 cents.

Cognitive Evaluation Theory (Deci & Ryan, 1991)

The way in which rewards are interpreted (evaluated) has an impact on intrinsic motivation

The same reward can be interpreted as

controlling (i.e., trying to influence their behaviour), resulting in decreased intrinsic motivation

informational (i.e., providing constructive feedback), resulting in enhanced intrinsic motivation

Which of these rewards are “controlling” and which are “informational”?

Coach: “Win and we skip tomorrow’s session”

Giving a prize for just showing up

Coach: “Your tackle timing improved; keep that footwork”

Giving a progress report with specific, constructive comments

Well… it depends on your cognitive evaluation (interpretation)!

But it’s likely that the first two will be interpreted as controlling and the last two as informational.

Over time, rewards can shape motivation

One can turn into the other

Further examples:

A toddler’s drawing activity becomes less enjoyable when rewards are introduced, as the focus shifts from the joy of drawing to earning the reward.

Volunteering becomes less enjoyable when it transitions to a paid activity, as the focus shifts from intrinsic satisfaction to the external reward.

Removing external rewards, such as points or badges, can renew interest in an activity when the activity itself is inherently enjoyable.

Hierarchical Model of Intrinsic/Extrinsic Motivation (HMIEM, Lalande & Vallerand, 2014)

Motivation operates at three hierarchical levels of generality (from most general to most specific):

Global level: how a person is generally motivated across life (e.g., traits)

Contextual level: within specific life domains (e.g., work, school, relationships, sport).

Situational Level: Motivation in specific situation, moments, or tasks within a certain context (e.g., studying for a test today).

| level | example |

|---|---|

| situational | specific drills, specific parts of the game |

| contextual | football |

| global | sport |

Similarity across levels. For example, high intrinsic motivation at the global level is associated with high intrinsic motivation at the contextual level

Small-group chats

- Share an example from your own experience where your motivation changed from intrinsic to extrinsic (or vice versa). What triggered the change?

- Think of an example from sport or exercise that fits all three hierarchical levels (just like in the table in the previous slide)

- Global: Motivation across life

- Contextual: Motivation within a specific sport or activity

- Situational: Motivation in a specific moment or task within that sport

Achievement Goal Theory (Nichols, 1984)

Two orientations (also known as “achievement goals”):

Task / mastery orientation: focus on aquiring competence and personal development

Ego / performance/outcome orientation: focus on demonstrating better performance than others

Examples:

“I will try to beat my own best lap time today” (Task orientation)

“I want to finish ahead of my teammates today” (Ego orientation)

The two orientations are associated with different behaviours and thoughts

| Orientation | Persistence (in spite of failure) | Moral behaviour | Perceived competence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Task | high | high | stable |

| Ego | low | low | unstable* |

Note

Task orientation is not the same as intrinsic motivation, and ego orientation is not the same as extrinsic motivation.

An ego oriented athlete can still be intrinsically motivated if they genuinely enjoy competition

Questionnaire activity (part 2)

This questionnaire measured your task and ego orientation

Complete page 2 of the questionnaire document to know your scores

Achievement Goal Theory (Nichols, 1984), continuation

Two climates (also known as “perceived demands”):

Climates are environments that facilitates or impede the development of a certain personal orientation.

- Task climate: rewards and punishments are contingent to development and effort

- Ego climate: rewards and punishments are contingent to distance from desired outcome

Typically, an ego climate fosters ego orientation, and a task climate fosters task orientation.1

Examples of task-climate cues:

- Effort and improvement praised

- individual progress charts

Examples of ego-climate cues:

- Public leaderboard and comparison

- mistakes punished publicly

Imagine this scenario and discuss in small groups

You are the psychologist of a youth football club. A football coach had previously emphasized competition among players, frequently posting public leaderboards and rewarding only those who outperformed others. Over time, athletes began to focus solely on winning, felt anxious about mistakes, immoral behaviour increased, and reported enjoying the sport less. Realizing the negative impact, the coach now asked for your help. What would you do? (Hint: shift from ego to task climate)

Here’s what you could do:

- Reward effort, improvement, and learning (e.g., through praises) rather than just outcomes

- Set individual progress goals and celebrate personal bests

- Introduce activities where success is measured by mastering new skills, not by comparison

- Reduce public comparisons and instead highlight collective achievements

Note

Note: an ego climate might be inappropriate in certain contexts (e.g., youth, leisure) but appropriate in other contexts (e.g., elite, competition)

Trichotomous model (Elliot, 1999)

The trichotomous model expands on previous theories by integrating three dimensions of motivation to provide a more detailed understanding of achievement-related behaviors.

Three dimensions:

- Orientation / achievement goal (task, ego),

- Climate / perceived demands (task, ego),

- Direction (approach, avoidance)

“Two-by-two model” (Elliot, 1999)

The two-by-two model combines two dimensions, orientation (task, ego) and direction (approach avoindance).

| Approach | Avoidance | |

|---|---|---|

| Task | Task-Approach | Task-Avoidance |

| Ego | Ego-Approach | Ego-Avoidance |

Example of “two-by-two model”

| Approach | Avoidance | |

|---|---|---|

| Task | Striving to learn a new skill | Striving to avoid decline in skill |

| Ego | Striving to outperform others | Striving to avoid doing worse than others |

:::

Attribution Theory (Weiner, 1986)

Attribution: explanation for why something happened

This model categorizes explanations against 3 dimensions, each defined in two levels:

- Locus of causality

- internal: due to individual characteristics

- external: due to something not pertaining to the individual

- Stability

- stable: it does not vary over time

- unstable: it varies over time

- Locus of control

- under own control: it can be changed by the individual

- outside own control: it cannot be changed by the individual

Examples of Attribution Theory

| Scenario | Locus of Causality | Stability | Locus of Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| “I failed the test because I didn’t study enough.” | Internal | Unstable | Under own control |

| “We lost the game because the referee made bad calls.” | External | Unstable | Outside own control |

| “I won the race because I have natural talent.” | Internal | Stable | Outside own control |

| “The project succeeded because the team worked hard.” | Internal | Unstable | Under own control |

Memory tip

How to remember the distinction between “Achievement Goal Theory” and “Attribution Theory”.

Both deal with successes and failures. The former is concerned with the what, the latter with the why.

Additional and optional: Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985)

Focuses on the degree to which human behavior is self-motivated and self-determined.

Three basic psychological needs:

- Autonomy: Feeling in control of one’s actions and decisions.

- Competence: Feeling effective and capable in one’s activities.

- Relatedness: Feeling connected to others and having a sense of belonging.

Very influential theory because it highlights the importance of basic psychological needs in fostering optimal functioning, well-being, and sustained engagement. It provides a framework for understanding how different types of motivation impact behavior and performance across various domains.