Foundations of executive functions

Dr Germano Gallicchio

Lecturer in Psychophysiology and Cognitive Neuroscience

School of Psychology and Sport Science, Bangor University, UK

profile | research | software | learning resources | book meeting

On a computer press F11 to de/activate full-screen view.

For smartphone and review: Bottom left menu → Tools → PDF Export Mode.

For pdf document: use “learning resources” link above.

Last modified: 2025-12-09

QR code to

these slides:

Agenda

definition of executive functions

brief anatomy of the executive functions

unity and diversity of executive functions

shifting

updating

inhibition

some executive function tasks

What are executive functions?

Set of higher order functions that control all cognitive processes

Like the director of an orchestra executive functions control:

which cognitive functions are silenced/heightened at a certain time

How cognitive functions are coordinated

Main function: executive functions allow to control behaviour, cognition, and emotions

Anatomy of the executive functions: a distributed network

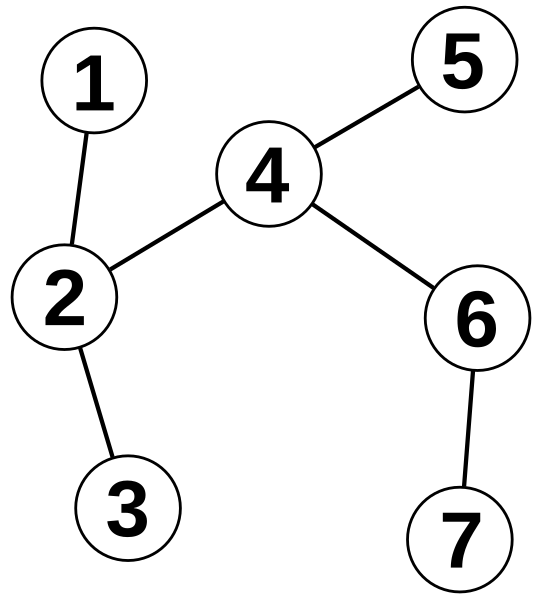

Executive functions rely on a distributed network, involving several cortical and subcortical regions (i.e., nodes of the network) and their connections (i.e., edges of the network).

Traditionally, the prefrontal cortex (often shortened as PFC) is attributed a the role of an important node within this network.

What cortical regions are fundamental to executive funtcions?

Key cortical regions along with the main functions they enable:

| Region | Abbreviation | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex | DLPFC | Working memory, goal maintenance, planning and top‑down control |

| Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex | VLPFC | Response selection, inhibition, and controlled retrieval |

| Orbitofrontal cortex | OFC | Value representation, reward-guided decision making and impulse control |

| Anterior cingulate cortex* | ACC | Conflict monitoring, error detection, and performance adjustment |

| Parietal cortex | - | Attentional reorienting, representation updating and integration with sensory information |

| Premotor cortex / supplementary motor area | SMA | Action selection and motor planning |

*Note: anatomically it lies just outside the prefrontal cortex but it works in synergy with it

Key subcortical regions are basal ganglia, thalamus, cerebellum

Optional evolutionary note

Inter‑species differences in the mass of the PFC relative to the whole cerebral cortex

Relative to total cortical mass, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) is disproportionately large in primates (and especially in humans).

This may be the neural substrate to the greater executive function skills in primates compared with non-primates.

However, a bigger structure does not always lead to better function. Connectivity is also important.

Frenology

Frenology is a historical theory, now discredited, suggesting that the shape and size of the skull can determine a person’s character and mental abilities.

Some key concepts:

- Localization of Function: Different areas of the brain are responsible for different traits and behaviours.

- Cranial Measurements: The bumps and indentations on the skull reflect the underlying brain structure.

Despite getting the wrong answer, phrenology gets the credits for sparking important questions about the localization (in the brain) of cognitive functions.

Neuropsychology first and neuroscience later confirmed that each cortical region plays key roles in networks responsible for specific cognitive functions.

Earlier evidence for the connection between structure and function came from lesion studies: clinical assessment of patients with selective lesions to the cerebral cortex.

The tragic story of Phineas Gage. A selective prefrontal-cortex lesion

The first well documented case of selective lesion to the PFC.

A railroad worker at the time. In an accidental explosion, a metal rod passed through his skull. He survived. But he became a different person.

Before the accident: responsible and smart.

After the accident: Able to walk and talk. But unable to control himself, impatient, impulsive, showing socially inappropriate behaviour, and no inhibition.

Unity and diversity of executive functions: Miyake et al. (2000)

Seminal study evaluating quantitatively the commonalities and differences among several multiple executive-function tasks and the functions they represent.

They used a variety of tasks to measure each of three functions, upon which there was growing consensus as being the core executive functions:

Two key conclusions:

the three core executive functions are separable: each explains a unique aspect of cognitive control.

the three core executive functions are correlated: each contributes to explaining general aspects of cognitive control.

This unity and diversity framework revolutionized how researchers conceptualize executive functions. Not as a single construct, but as three separable but moderately correlated functions.

Inhibition

Inhibition refers to the ability to suppress dominant responses that are inappropriate or not relevant in a certain situation.

How you might experience inhibition:

- Resisting the urge to check your phone while studying

- Stopping yourself from eating a slice of cake when you are trying to eat healthy

- Not doing something that you normally do out of habit

- Not laughing during a serious or inappropriate moment

Key properties of inhibition tasks:

- You are presented with stimuli that contain two pieces of information (e.g., the word “high” spoken in either a high-pitched or low-pitched voice)

- Sometimes, the two pieces point at the same idea (congruent trial, e.g., the word “high” spoken in a high-pitched voice)

- Sometimes, the two pieces point at different ideas (incongruent trial, e.g., the word “low” spoken in a high-pitched voice)

- One of the two pieces is dominant; the one that is more automatic or habitual to process (e.g., the word meaning)

- Your task is to focus only on the non-dominant information.

- Congruent trials present no inhibitory challenge because the two pieces of information match.

- Incongruent trials require solving a conflict between the to-be-inhibited dominant response and the required non-dominant response.

Key performance metric:

- Inhibition cost: how slower and less accurate you become in incongruent vs congruent trials. In other words, the cost of solving the conflict by inhibiting the dominant information/response.

Measuring inhibition through the Stroop task

The Stroop task involves a conflict between the meaning of a word and the color of the ink it is printed in.

Key features in a trial:

- Stimulus: Words that represent colors printed in in/congruent colors (e.g., the word “red” printed in blue ink).

- Decision: Name the color of the ink, not the word itself.

- Response: Press the key corresponding to the color of the ink.

Key outcome measures:

- Inhibition cost (response time): time taken to respond correctly to incongruent trials minus time taken to respond correctly to congruent trials.

- Inhibition cost (accuracy): proportion of correctly responded incongruent trials minus proportion of correctly responded congruent trials.

There are variations:

- Different types of stimuli (e.g., shapes, numbers, visual/auditory modality).

optional Stroop task demonstration

Measuring inhibition through the Flanker task

The Flanker task involves resolving a conflict between a central target stimulus and surrounding flanking stimuli.

Key features in a trial:

- Stimulus: A central arrow (or letter) flanked by other arrows (or letters) that point in the same (congruent) or opposite (incongruent) direction.

- Decision: Identify the direction of the central arrow while ignoring the direction of the flanking stimuli.

- Response: Press the key corresponding to the direction of the central arrow.

Key outcome measures:

- Inhibition cost (response time): time taken to respond correctly to incongruent trials minus time taken to respond correctly to congruent trials.

- Inhibition cost (accuracy): proportion of correctly responded incongruent trials minus proportion of correctly responded congruent trials.

There are variations:

- Different types of stimuli (e.g., arrows, letters, fish).

- Different numbers of flankers (e.g., 2 vs 4 flanking stimuli).

Flanker task demo

Updating

Being able to maintain and manipulate information in working memory.

How you might experience updating:

Mental arithmetic: keeping track of running totals while calculating (e.g., ,mentally adding up the cost of items in a shopping basket)

Phone number exchanging: memorizing a phone number you have just been told, except they tell you “sorry, the third to last digit was 5”

Navigation: remembering the sequence of turns you have taken to find your way back

Key properties of updating tasks:

- You are presented with a sequence of stimuli (e.g., letters, numbers, spatial positions)

- You must continuously maintain and update a mental representation of recent items

- The task requires you to discard old information and replace it with new information

- At some point, you must recall or recognize items from recent positions in the sequence

Key performance metrics:

- Accuracy: how correctly you can recall or recognize items at specified positions (e.g., an n-number of items back)

- Response time: how quickly you can respond when probed

Measuring updating through the n-back task

You see a continuous stream of stimuli (e.g., letters, digits, sounds, or locations). Each stimulus is presented for a short duration, and there might be a small gap until the next stimulus.

Your task: for each stimulus, decide if the current item matches (i.e., is identical to) the one from n steps earlier. A stimulus requiring a decision forms a trial.

Common levels:

- 1‑back (compare with the immediately previous item)

- 2‑back (compare with the item two steps back)

- 3‑back+ (increasing working‑memory load)

Key features in a trial:

- Stimulus appears briefly, then a short gap

- Decision: match vs non‑match with the item n ago

- Response: one key for match, another for non‑match (or just one key for matching stimuli and withhold response for non-matching stimuli)

Stimulus modalities:

- Visual symbols (letters/digits)

- spatial positions (spatial n‑back)

- tones (auditory),

- a combination (dual n‑back)

Key outcome measures:

- Accuracy (number of correctly responded trials divided by the number of total trials)

- response times (time from the onset of the stimulus to the correct response within each trial)

There are variations:

- Dual n‑back (simultaneous auditory + visual streams)

- Adaptive n‑back (n increases/decreases based on performance)

optional n-back task demonstration

Shifting/switching

Being able to flexibly switch between tasks or rules.

How you might experience shifting:

Language: switching language when translating to/from two languages

Driving: shifting from following the navigation system to reacting to unexpected roadworks

Home life: pausing cooking to answer the door

Navigation on phone: switching from map view to messages and back

Sports: switching from offense to defense

Key properties of switching task:

- You are described two tasks, A and B.

- For each task, you are given a set of stimuli that require a decision and then a response. Each set of stimuli requiring a decision/response is called a trial.

- Sometimes, you are asked to do task A, other times you are asked to do task B.

- In a block, you might be presented with only task A trials (pure trials). This is a pure block.

- In another block, you might be presented with some task A trials and some task B trials. This is a mixed block. In other words, some trials will require you to continue performing whichever task you were doing until then (repeat trials) or to switch to the other task (switch trials)

Key performance metrics:

Switch cost: how slower and less accurate you are in switch trials vs repeat trials

Mixing cost: how slower and less accurate you are in repeat trials vs pure trials

Measuring shifting through the digit-letter task

You are presented with a pair of a digit and a letter (e.g., 3T).

Task A: Digit task

- Stimulus: a digit (e.g., 3, 7)

- Decision: Is it odd or even?

- Response: Press left key for odd, right key for even

Task B: Letter task

- Stimulus: a letter (e.g., A, G)

- Decision: Is it a vowel or consonant?

- Response: Press left key for vowel, right key for consonant

How they alternate:

- Cue tells you which task to perform (e.g., colored box, position on screen)

- Pure blocks: only digit trials OR only letter trials

- Mixed blocks: digit and letter trials alternate unpredictably or in a sequence

There are variations:

- Different stimulus types (numbers/letters, shapes/colors)

- Different cue types (verbal, spatial, color-coded)

- Predictable vs unpredictable switches

- Different cue-stimulus intervals

optional digit-letter task demo

Measuring shifting through the dual task

You are presented with a spoken number (e.g., “three”, “eight”).

Task A: Odd/Even Task

- Stimulus: A number spoken aloud (e.g., 3, 7, 8)

- Decision: Is it odd or even?

- Response: Press left key for odd, right key for even

Task B: Magnitude Task

- Stimulus: A number spoken aloud (e.g., 3, 7, 8)

- Decision: Is it greater than or less than five?

- Response: Press left key for less than five, right key for greater than five

How they alternate:

- A cue tells you which task to perform (e.g., different voice)

- Pure blocks: only odd/even trials OR only magnitude trials

- Mixed blocks: odd/even and magnitude trials alternate unpredictably or in a predictable sequence

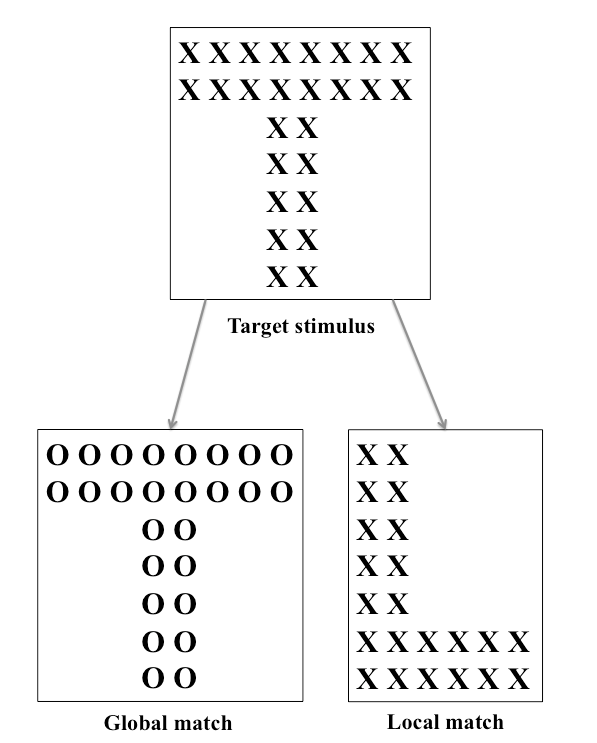

Measuring shifting through the global-local task

You are presented with a Navon stimulus.

Navon stimuli consist of large letters or shapes made up of smaller letters or shapes. For example, a large “H” might be composed of many small “S” letters.

This design allows for two levels of processing: the global level (the large letter) and the local level (the small letters).

Task A: Global Task

- Stimulus: A Navon figure.

- Decision: Identify the large letter.

- Response: Press a designated key corresponding to the identified letter.

Task B: Local Task

- Stimulus: The same or a different Navon figure.

- Decision: Identify the small letters.

- Response: Press a designated key corresponding to the identified letter.

How they alternate - A cue tells you which task to perform - The cue could be the colour of the Navon figure or the tone of a sound

Find the executive functions in real scenarios

In small groups, pick a scenario and map each activity to an executive function (note: an activity could map onto more than one executive function).

Olympic gymnast:

- Learning new routine while maintaining old ones

- Suppressing fear responses on difficult elements

- Adjusting performance based on judges’ feedback

Air Traffic Controller

- Tracking planes

- Switching attention between radio channels

- Updating mental model as new planes enter airspace

a student

- Resisting social media distractions

- Switching between different subjects

- Tracking what’s been studied vs. what remains

Beyond the core executive functions

The three core executive functions studied by Miyake et al. (2000) are important because they can be considered building blocks for higher-order functions, but they are not exhaustive.

Some additional functions considered executive functions include:

Planning and problem solving

Goal setting and maintenance

Performance monitoring and error detection

Cognitive flexibility beyond simple shifting (e.g., creativity)

Decision‑making and value‑based control in some models